Red Aban Timeline

Trace the events of the "Red Aban" uprising, from the initial fuel shock to the brutal crackdown that the regime tried to bury under a total internet blackout.

Red Aban Timeline

In November 2019, the rulers of the Islamic Republic tried to break the people of Iran with a midnight fuel price shock, bullets in the streets, and one of the most brutal internet blackouts in the world. Many of us now call those days “Bloody Aban” or “Red Aban” – a week when unarmed protesters were shot, the country was cut off from the outside world, and families were left to bury their dead in silence [1][2][7][8][10].

This timeline is written from the side of the people who were targeted, not from the side of the regime that killed protesters and tried to hide the evidence behind a digital curtain [1][2][6]. It pulls together work by human rights organizations, independent journalists, and network measurement projects so that the sequence of those days can be seen clearly and used in graphics, archives, and campaigns [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][9].

What happened in Red Aban did not end in 2019. Since then, the regime has upgraded its firewall, refined its shutdown tactics, and repeatedly used mobile blackouts and platform blocks against new waves of protest, especially since 2021 and the 2022 uprising after the killing of Jina (Mahsa) Amini [0][12][13][14]. The wounds from November 2019 are still open, and the techniques tested that week are still being used against people today [2][6][12][13].

How to read this timeline

- Dates are given in both the Gregorian and the Iranian calendars where useful.

- Times are Tehran local time (UTC+3:30) and based on public reporting and network measurements, not on official claims by the Islamic Republic.

- The focus is on what can be supported by documented evidence from independent and international sources, not regime statements [1][2][4][6][9].

Chronology

1. The Trigger: Fuel Price Hike

15 November 2019 / 24 Aban 1398

-

Around 00:00

In the middle of the night, without public debate or warning, the authorities announce a sudden change in gasoline policy [8][11].- A rationing system is introduced.

- The subsidized (quota) price per liter is raised by roughly 50 percent.

- The price for fuel beyond the ration jumps to roughly triple the previous level.

Under the new scheme, the first 60 liters per month cost 1,500 Tomans per liter, while additional fuel costs 3,000 Tomans [8][11].

The announcement hits a population already under heavy economic pressure, and it is clearly timed to minimize immediate reaction.

-

Morning to afternoon

The news spreads fast. State TV repeats the price tables; messaging apps and social media circulate screenshots and videos explaining the change [8][11].

People discuss the hike as an attack on the working poor, taxi drivers, and anyone who depends on cars for survival. -

Evening and late night

First scattered protests and road blockages are reported in multiple cities, including Sirjan and Ahvaz [1][2][8].

In Sirjan, protesters move toward a fuel depot; security forces respond with live fire, killing at least one person on the first night of unrest [1][2][8].

Videos and reports show anger not just at fuel prices, but at the entire system that imposed them [2][8].

2. Day One of Open Revolt

16 November 2019 / 25 Aban 1398

- Around 09:00–14:00

Protests spread into a nationwide wave. Demonstrations, roadblocks, and sit-ins are reported in dozens of cities across the country, including Tehran, Tabriz, Isfahan, Shiraz, Karaj, Kermanshah, Mashhad, Ahvaz, and others [2][8].

Crowds gather at major junctions, highways, and squares. In many places drivers block roads with their cars. Slogans move quickly from “No to expensive fuel” to open rejection of the ruling system [2][8].

-

Around 14:00–18:00

Banks, government buildings, and regime symbols are attacked or set on fire in some locations, especially where security forces have fired on crowds [2][8].

Human rights organizations later document widespread use of live ammunition by security forces in several cities, including shootings from rooftops and moving vehicles, and firing at close range into crowds [1][2][7].

The death toll begins to rise sharply, although the full scale will only be known months later [1][2]. -

Around 16:00–20:00

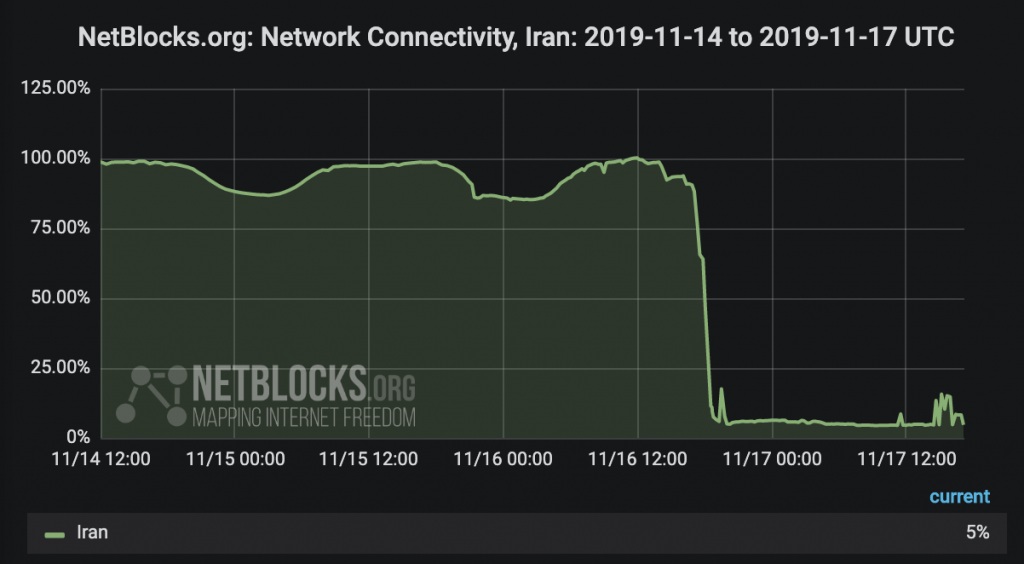

Significant disruptions to the global internet are first measured. Users report difficulty connecting to foreign services, while some domestic services remain reachable [4][6][9].

Network data shows a progressive decrease in international connectivity as major providers begin to limit traffic [4][6][9]. -

Around 22:15 (about 18:45 UTC)

NetBlocks reports that national connectivity in Iran has dropped to about 7 percent of ordinary levels after around twelve hours of escalating network disconnections [4][9].

At this point, Iran is effectively entering a near total national internet shutdown, just as security forces intensify their crackdown [2][4][6][9].

3. Deep Blackout, Mass Killings

17 November 2019 / 26 Aban 1398

-

00:00–24:00

The blackout hardens into a digital wall. NetBlocks and other observatories estimate that national connectivity remains around 5 percent of typical traffic, leaving most people unable to reach the global internet [4][6][9].

Major mobile networks such as MCI, Rightel, and Irancell are reported as largely offline for international traffic across the country [4][6][9]. -

Throughout the day

Because almost all foreign-facing connectivity is cut, images and videos from this day surface only much later.

Amnesty International and other organizations eventually reconstruct dozens of incidents where security forces use live fire and lethal force against protesters and bystanders in cities across Iran, including Mahshahr, Shiraz, Karaj, and others [1][2][7].

Families describe bodies being taken directly from hospitals to unknown locations, security forces present at funerals, and pressure not to speak to the media [1][2][6][7]. -

Later reconstructions

Amnesty International concludes that more than 220 out of at least 304 documented deaths occurred on 16 and 17 November alone, during the most intense phase of both the crackdown and the internet shutdown [1][3][6].

The combination of bullets in the streets and darkness online becomes the defining pattern of Red Aban [1][2][6].

4. 52 Hours in the Dark

18–19 November 2019 / 27–28 Aban 1398

-

By 18 November (about 52 hours into the shutdown)

NetBlocks reports that Iran has been largely offline for more than two days, with connectivity still around 5 percent of normal levels [4].

The shutdown is described as a government ordered, near total national blackout targeting widespread public protests [2][4][6][9]. -

By 19 November

Analysis based on traffic data used by international media estimates connectivity at roughly 4 percent of ordinary levels, showing how little information is escaping the country [6][9].

Amnesty International releases early evidence that security forces are using lethal force and reports at least 106 people killed, a figure that will later be revised upward as more cases are verified [2][6].

On the ground, people continue to protest in many cities, but they cannot easily show the world what is happening [1][2][6].

5. Crushed Under Blackout

20 November 2019 / 29 Aban 1398

-

All day

Iran remains in a near total shutdown. NetBlocks reports national connectivity still stuck around 5 percent of normal levels, and notes that some of the remaining networks are being cut or further restricted [4][9].

Under cover of this blackout, security forces continue to use lethal force in various parts of the country [1][2][7][8]. -

Mahshahr and other hotspots

Rights organizations and later investigations describe particularly intense violence in and around the city of Mahshahr in Khuzestan province. Reports indicate that security units surrounded protesters, pursued them into surrounding areas, and fired on them as they tried to flee [1][2][7][8].

Because of the blackout and fear of reprisals, many survivors and families are only able to speak after connections are restored or once they have reached safer channels [1][2][6][7].

6. First Cracks in the Wall

21–22 November 2019 / 30 Aban – 1 Azar 1398

-

From 21 November onward

Technical measurement data shows a slow, uneven restoration of connectivity. Observatories such as OONI and NetBlocks report that limited traffic from some provinces begins to reach the global internet again, though at very low levels compared to normal [5][6][9].

In practice, some fixed-line connections in certain urban areas regain partial access, while many users, especially those relying on mobile networks, remain effectively cut off [5][6][9][12]. -

National connectivity still under 10 percent

NetBlocks notes that even after these first signs of restoration, national connectivity is still estimated at less than 10 percent of ordinary levels [5][9].

For many people, it still feels like living inside a sealed country with only narrow cracks in the wall.

7. Partial Reconnection, Flood of Evidence

23 November 2019 / 2 Azar 1398

-

Fixed-line connections return in force

NetBlocks confirms that, by 23 November, fixed-line connectivity has risen to around 64 percent of normal traffic after a week of near total shutdown [5].

Mobile internet, however, remains heavily restricted and unstable in many areas [5][6][9]. -

The videos finally get out

As more fixed-line routes reopen, larger volumes of videos, photographs, and testimonies from the protests and the crackdown begin to reach the outside world [2][5][6].

Amnesty International and other groups collect, verify, and geolocate footage from at least 31 cities, documenting repeated use of live fire, plainclothes forces, and security units shooting at unarmed people [2][6].

What the regime tried to hide during the blackout starts to become visible, frame by frame [2][6][7].

8. Aftermath: Counting the Dead, Building a Higher Wall

Late 2019 – 2020

-

Documenting the dead

Over the following months, Amnesty International identifies at least 304 men, women, and children killed between 15 and 18 November 2019, based on interviews with families and witnesses, analysis of video evidence, and review of official documents where possible [1][3][10].

Amnesty stresses that the real number is likely higher, given intense pressure on families not to speak and the difficulty of accessing information from many parts of the country [1][2][6][7]. -

Higher estimates

Reuters, citing unnamed Iranian officials, reports that internal figures used by authorities point to around 1,500 people killed, including at least 17 teenagers and about 400 women, although this number has never been transparently documented and is denied by the regime [8].

Human Rights Watch notes in 2020 that there has been no credible, transparent domestic investigation into the killings and no meaningful accountability for members of the security forces involved [7]. -

Mass arrests and torture

Rights organizations document thousands of arrests in the weeks and months after the protests. Reports describe torture and ill-treatment in detention, forced confessions, and unfair trials of protesters, activists, and bystanders swept up in the crackdown [1][2][7].

Families and survivors face harassment, surveillance, and threats when they try to tell their stories or commemorate those who were killed [1][2][6][7].

2020–2025: From blackout to upgraded firewall

-

Shutdowns as a standard weapon

Digital rights groups show that, after November 2019, the Islamic Republic increasingly uses targeted mobile shutdowns and regional blackouts during protests, especially in provinces such as Khuzestan, Kurdistan, and Sistan and Baluchistan [12][16].

What was tested at national scale in Red Aban becomes a standard part of the regime’s toolkit: cut the internet where people resist, then send in the forces [2][12][16]. -

New layers of blocking and surveillance

Technical reports from OONI and other observatories document how, during the 2022 protests after the killing of Jina (Mahsa) Amini, authorities intensified blocking of encrypted DNS, and newly blocked platforms like WhatsApp and Instagram that had previously remained accessible [0][13].

Measurements show both TLS-level interference and DNS tampering against domain-based services, and a growing reliance on the National Information Network to keep domestic services running while cutting people off from the open internet [6][13][14]. -

From Red Aban to today

By 2025, analysts describe the evolution from the blunt “pull the plug” shutdown of 2019 toward more sophisticated “stealth blackout” and high-granularity filtering tactics that seek to preserve regime infrastructure and some domestic connectivity while isolating protesters and hiding repression [0][2][6][12][14].

For those of us who oppose this regime, Red Aban is not just a memory. It is the week when the enemy openly showed how far it would go, and when a new era of digital control over Iran’s streets, phones, and lives began [2][6][12][13].

References

[0] Open Observatory of Network Interference. (2022, November 29). Technical multi-stakeholder report on Internet shutdowns: The case of Iran amid autumn 2022 protests. OONI. Source

[1] Amnesty International. (2020, May 20). Iran: Details released of 304 deaths during protests six months after security forces’ killing spree. Amnesty International. Source

[2] Amnesty International. (2020, November 16). A web of impunity: The killings Iran’s internet shutdown hid. Amnesty International. Source

[3] Amnesty International. (2020, November 16). Iran: Internet deliberately shut down during November 2019 killings – new investigation. Amnesty International. Source

[4] NetBlocks. (2019, November 15). Internet disrupted in Iran amid fuel protests in multiple cities. NetBlocks. Source

[5] NetBlocks. (2019, November 23). Internet being restored in Iran after week-long shutdown. NetBlocks. Source

[6] Open Observatory of Network Interference. (2019, November 23). Iran’s nation-wide Internet blackout: Measurement data and technical observations. OONI. Source

[7] Human Rights Watch. (2020, November 17). Iran: No justice for bloody 2019 crackdown. Human Rights Watch. Source

[8] Wikipedia contributors. (2024). 2019–2020 Iranian protests. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Source

[9] Wikipedia contributors. (2024). 2019 Internet blackout in Iran. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Source

[10] Al Jazeera. (2019, December 17). “Vicious crackdown”: Iran protest death toll at 304, Amnesty says. Al Jazeera. Source

[11] Fassihi, F., & Gladstone, R. (2019, November 15). Iran abruptly raises fuel prices, and protests erupt. The New York Times. Source

[12] ARTICLE 19. (2022, November 17). Iran: New tactics for digital repression as protests continue. ARTICLE 19. Source

[13] Open Observatory of Network Interference. (2022, September 25). Iran blocks social media, app stores and encrypted DNS amid Mahsa Amini protests. OONI. Source

[14] Shababi, S. (2020, December 14). Shatter the web: Internet fragmentation in Iran. Middle East Institute. Source

[16] Advocacy Assembly. (2022, November 16). Iran protests: 5 things to know about internet shutdowns. Advocacy Assembly. Source